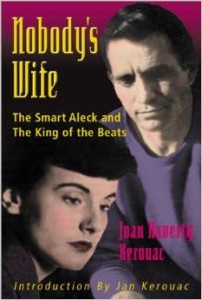

Becoming friends with the remarkable Jan Kerouac was one of the great pleasures for me in acting as the editor for her mother’s book (Nobody’s Wife: The Smart Aleck and the King of the Beats, by Joan Haverty Kerouac—see my last blog post).

When Jan’s brother David allowed me to take the treasure box of Joan’s manuscript pages, both he and I knew my first challenge would be to convince Jan that I was capable of a huge job. The manuscript was a mountainous mess of paper. It required somebody to care about it, to give attention to every detail, to step it tenderly through a complex range of editing issues: sorting and indexing the pages, transferring them from typescript to computer, comparing multiple versions, revising, rewriting, sequencing, compiling, and proofing. And once those tasks were done, there would remain the mission of selling it to a publisher.

Jan Kerouac was already an accomplished novelist when I had my first nervous phone conversation with her in 1993. The two novels published during her lifetime, Baby Driver (1981) and Trainsong (1988) established her as an outstanding literary talent. Both these books shed light on the close, tangled relationship between Jan and her mother Joan. What Jan most earnestly wanted was to edit her mother’s manuscript herself.

But Jan was in very poor health, from kidney failure and other issues. She was on dialysis for as long as I knew her. Her mother’s death had been profoundly difficult for her. She knew Joan had been writing a memoir, but she didn’t have the strength to do the work that would be required to get it ready for publication. So she listened to me cautiously, guardedly, to evaluate whether I had the passion and the talent and the technical skills to take charge of her mother’s legacy. She talked with me until she was satisfied she could trust me, and then she gave me her blessing. She guided her brother and her sisters into giving me the go-ahead as well, so the entire family was on board.

If she couldn’t edit her mother’s book herself, Jan was at least determined to write the introduction for it. Her name carried weight; it would help the manuscript find a home. But Jan was so weak and ill, she wasn’t able to use a typewriter or keyboard any more. So over the course of months, Jan recorded the words of her introduction using a portable cassette tape recorder. She recorded in the bath sometimes, or sitting in a rocking chair outside her New Mexico home. She delivered a beautiful, heartfelt piece of work to me on a 20-minute cassette tape. Listening to Jan’s words, transcribing these sweet and intimate reminiscences about her mother, helped fill me with the determination to see this project through to success.

In my previous blog post, I talked about how “Joan Haverty Kerouac” was the author’s name we put on a manuscript written by a woman who called herself Joan Stuart. Joan’s daughter Jan was another woman who had last-name issues. Jan didn’t meet her famous father, Jack Kerouac, until she was ten years old. Jack had denied paternity all Jan’s life, despite a court order and proof from a blood test. Running away from home at age 16, Jan boldly showed up on Jack’s doorstep. She spent a drunken afternoon with him. Jan told Jack she might like to write some day. “Use my name,” Jack memorably told her. Jan didn’t take the name Kerouac until she became a writer.

Jan and I talked on the phone often while I worked through Joan’s manuscript, organizing sentences and pages and chapters into a coherent whole. I got to meet her in person only one time. Jan and I attended the Beat Generation conference at New York University in summer 1994. We gave away small hand-printed chapbooks that contained chapter 12 of Nobody’s Wife—“the wedding chapter”—and Jan read from Joan’s manuscript in a panel on Women and the Beats.

We met with a couple of publishing bigwigs. As a charismatic, well-respected novelist, Jan had some great contacts. As a member of the Kerouac bloodline, though, she had no pull whatsoever. The Jack Kerouac estate entirely excluded her. Not one item, not one dollar passed from Jack to his only daughter.

Jan led a principled objection to the way Jack Kerouac’s manuscripts and belongings were being sold off piecemeal for scandalous amounts of money. She advocated that the whole literary estate should be in an academic library with access for scholars. Jan increasingly found doors closed to her as she continued to oppose the workings of the Jack Kerouac estate, speaking out in opposition to the sale of literary history to private collectors.

We didn’t find a publishing contract for Nobody’s Wife at the NYU Beat Generation conference, but we found one soon afterward. In my last phone conversation with Jan Kerouac, I gave her good news. Creative Arts Book Company accepted the manuscript and offered a generous advance. Jan struggled to let me know how delighted she was. She sounded unbearably tired.

Jan passed away in an Albuquerque hospital only a few days later, on June 5, 1996.

The unfortunate postscript: Publication of Nobody’s Wife was delayed four more years as a sad circumstance of Jan’s death. Since she had written the book’s introduction, the fate of the book was tangled up in legal issues related to Jan’s own literary estate. These issues weren’t resolved in court until 2000. That’s when Nobody’s Wife finally saw the light of day, and many found it a fitting tribute to the memory and determination of Jan Kerouac.